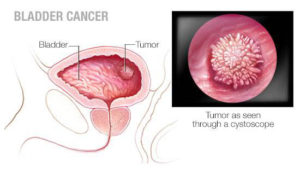

Bladder Cancer

Cancer of the Urinary Bladder arises from the inner lining of the bladder, known as the urothelium, and the most common presenting symptom is painless blood in the urine, or ‘haematuria’

Bladder Cancer, often referred to as urothelial cancer, is a relatively common cancer. As mentioned, the usual presenting symptom is blood in the urine, or haematuria , which is usually painless in nature. Many patients with early bladder cancer may not have visible blood in their urine, but may be found to have microscopic haematuria on routine urine testing by their doctor.

A number of risk factors for bladder cancer have been identifed over the years. The most common risk factor by far in the Australian population, is long term smoking. Cancer causing agents, or carcinogens, are inhaled through the lungs and then make their way into the blood stream. The carcinogens are then excreted in the urinary and end up sitting in the urinary bladder, which stores urine. Over many years, this exposure changes the bladder lining so tumours can arise. Other risk factors for bladder cancer include exposure to:

A number of risk factors for bladder cancer have been identifed over the years. The most common risk factor by far in the Australian population, is long term smoking. Cancer causing agents, or carcinogens, are inhaled through the lungs and then make their way into the blood stream. The carcinogens are then excreted in the urinary and end up sitting in the urinary bladder, which stores urine. Over many years, this exposure changes the bladder lining so tumours can arise. Other risk factors for bladder cancer include exposure to:

- dyes used in hairdressing, printing and textile industries (this is much less common nowadays due to improved workplace safety)

- radiation (a treatment used for pelvic cancers in men and women)

- cyclophosphamide, a chemotherapy drug.

It is about three times more common in men than women, and is not considered to be a hereditary condition.

While some suspected bladder cancers may be detected on a CT scan or ultrasound scan of the bladder, it can only be properly diagnosed by a procedure called cystoscopy, which involves placing a a small scope via the bladder outlet, or urethra, into the bladder to directly assess the bladder lining. If a tumour is found it can usually be removed through the same channel, which is termed transurethral or endoscopic resection. The tumour is then sent to a pathologist for testing and this helps to determine what further treatment the patient will require. Even if a bladder tumour has been fully removed by transurethral resection, there is a significant chance (30-80 percent) that the tumour could recur in the bladder, so bladder cancer patients generally need to undergo regular cystoscopies to monitor for tumour recurrence.

Bladder cancer can be divided into two main types-slower growing, non-aggressive (low grade) or aggressive (high grade). Low grade tumours can usually be managed by regular check cystoscopies, but higher grade tumours often require additional treatment to prevent them from recurring or progressing, in the form of ‘intravesical therapy’.

Intravesical therapy involves injecting chemotherapy agents, or a substance called BCG, directly into the bladder via a catheter in the urethra, so that the fluid comes in contact with the entire bladder lining, and kills any residual cancer cells that may still be present in the bladder. Intravesical therapy may be administered in hospital, immediately after a tumour has been removed from the bladder or it may be performed as an outpatient treatment through a hospital clinic.

As mentioned above, bladder cancers arise from the inner lining of the urinary bladder, called the urothelium. The majority of tumours will initially grow inwards into the cavity of the bladder and these are referred to as ‘superficial’ tumours, because they do not involve the deeper layers of the bladder wall. However many high grade tumours if not picked up in time, will start to grow below the bladder lining into the deeper layers of the bladder wall, and these are termed ‘invasive’ tumours.

Invasive bladder cancer is a life-threatening condition, as it has a propensity to spread beyond the bladder to other parts of the body. These tumours are treated with much more major surgery than superficial tumours, usually involving complete removal of the bladder and reconstruction of the urinary tract. Other treatments for invasive bladder cancer include radiation therapy or intravenous chemotherapy.